In this blog post I will explain how you can make an Angular app work with WebAssembly code. This combination of technologies can bring interesting advantages to web development and it is fairly simple to implement.

As I write this post, Angular is currently at version 5.1 and WebAssembly is still in its initial version, but it is making fast progress since Chrome, Edge, Firefox, and WebKit have reached a consensus on the binary format and API (see their roadmap).

Create the Angular App

Let’s start with the Angular app. If you are not familiar with Angular, you should visit its website and read its quick start guide and related documentation. You should be able to easily create a boilerplate app with the ng command (see angular CLI). We can start creating a new project called “ng-wasm”:

ng new ng-wasm

The generated project will have some basic source code and configuration files ready to be used. You should be able to serve the app right away and test it with the following command:

ng serve --open

The app should load on the web browser at http://localhost:4200/

Create the WebAssembly Code

The second step now is the creation of the WebAssembly code. If you are not familiar with WebAssembly, you should visit their website and go through the documentation. You will have to download and install the emsdk package.

Angular will need access to the WASM code we will create, so the easiest solution for us is to create a cpp folder inside the src folder of the Angular project. The Angular project should then have a structure that looks like this:

ng-wasm/

+-- e2e/

+-- node_modules/

+-- src/

+-- app/

+-- assets/

+-- cpp/ <-- NEW FOLDER

+-- environments/

Inside the cpp/ folder let’s create a file called main.c with the following C code:

#include <string.h> #include <emscripten/emscripten.h> double EMSCRIPTEN_KEEPALIVE multiply(double a, double b) { return a * b; } int EMSCRIPTEN_KEEPALIVE get_length(const char* text) { return strlen(text); } int main() {}

Basically we have implemented two C functions that we will be able to call from Angular. Note that we have to decorate these functions with EMSCRIPTEN_KEEPALIVE, which prevents the compiler from inlining or removing them.

emcc \

-O3 \

-s WASM=1 \

-s "EXTRA_EXPORTED_RUNTIME_METHODS=['ccall']" \

-o webassembly.js \

main.c

Note that I compile the C code with optimizations on (-O3 parameter), which makes the output more compact and efficient (if possible). The WASM=1 option tells the compiler to generate WebAssembly code (without this parameter, it would generate asm.js code instead). The EXTRA_EXPORTED_RUNTIME_METHODS=[‘ccall’] option is needed because we want to call the C functions from Javascript using the Module.ccall() javascript function (see the Angular code in the next section). I encourage you to read more about these parameters and play with them in order to see what errors or changes you will get.

- webassembly.js — Javascript glue code that helps loading the webassembly code (wasm)

- webassembly.wasm — Intermediate binary code to be used by the browser to generate machine code

The WebAssembly code is now ready to be used. Let’s go back to the Angular project now.

Modify the Angular Project

The default project created by the angular CLI contains an app/ folder with the following contents (among other files):

ng-wasm/

+-- src/

+-- app/

+-- app.component.ts

+-- app.component.html

+-- app.component.css

Let’s change the app.component.ts file to have the following code:

import { Component } from '@angular/core'; declare var Module: any; @Component({ selector: 'app-root', templateUrl: './app.component.html', styleUrls: ['./app.component.css'] }) export class AppComponent { multiplyResult: number; getLengthResult: number; multiply(a: number, b: number): void { this.multiplyResult = Module.ccall( 'multiply', // function name 'number', // return type ['number', 'number'], // argument types [a, b] // parameters ); } getLength(s: string): void { this.getLengthResult = Module.ccall( 'get_length', // function name 'number', // return type ['string'], // argument type [s] // parameter ); } }

In this code we implement two methods of the AppComponent class that will forward the call to our WebAssembly code generated in the previous section.

The first thing you should notice is the “declare var Module: any” at the top of the file. This is the typescript way of saying “there is a global variable named Module that I want to use in this scope”.The Module variable is actually a Javascript object used by the WebAssembly glue code. We declare it using type “any” because we don’t want typescript to complain about the things we will do with it. You should NOT do that in production code. It should be fairly simple for you to create a typescript definition file with class and method signatures (see my previous blog post where I discuss this).

Inside the multiply() member function we can call WebAssembly code using the Module.ccall() javascript function:

Module.ccall(

'multiply', // function name

'number', // return type

['number', 'number'], // argument types

[a, b] // parameters

);

In such call we pass the function name, return type, argument types and actual parameters to the binary function.

Now let’s change the app.component.html code in order to build our user interface:

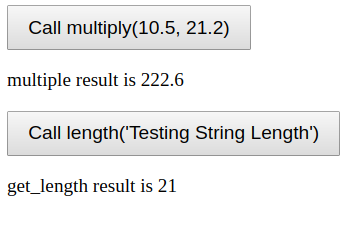

<button (click)="multiply(10.5, 21.2)"> Call multiply(10.5, 21.2) </button> <div *ngIf="multiplyResult"> multiply result is {{ multiplyResult }} </div> <button (click)="getLength('Testing String Length')"> Call length('Testing String Length') </button> <div *ngIf="getLengthResult"> get_length result is {{ getLengthResult }} </div>

This HTML code adds two buttons to the page. The first button will call the multiply() function with two parameters (10.5 and 21.2), and the second button will call the getLength() function with “Testing String Length” parameter.

The Last Step

If you try to serve the existing source code with the ng serve command, you will notice that Angular doesn’t automatically load the WebAssembly code we have added to the src/cpp/ folder. We have to manually change the index.html file (inside the src/ folder) and add the following code snippet to the end of the <head> section:

‹script› var Module = { locateFile: function(s) { return 'cpp/' + s; } }; ‹/script› ‹script src="cpp/webassembly.js"›‹/script›

This code imports the Javascript glue code generated by the WebAssembly compiler, but it also defines a Module.locateFile() function that will be used by WebAssembly to find the WASM file. By default, WebAssembly will try to find the WASM file at the root level of the application. In our case, we keep that file inside the cpp/ folder, so we have to prepend that folder’s name to the file path.

Now everything should be fine to go and the app should look like the screen below (with a bit of CSS makeup).

Conclusion

Angular and WebAssembly are two great technologies that can be used together without too much effort. There is no secret in this combination since both technologies are designed to work with web browsers and Javascript code is a common byproduct of their operations.

WebAssembly is still under development, but it has a huge potential towards native code performance, which is a dream yet to come true for web applications. Its roadmap is full of amazing features that serious web developers should never turn their back on.